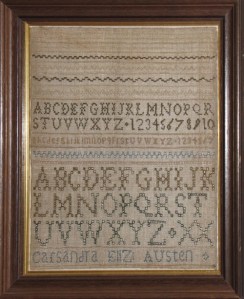

A needlework sampler survives with the maker’s name Jane Austen stitched within it: is this THE Jane Austen? Austen experts already have their doubts, and an alternative possible attribution, but I dare to venture into the debate because I bring two relevant skill sets to the question which have not been employed in the discussion so far.

The sampler has a stitched date of 1797, when author Jane would have been 22 years old: long past the age of making samplers. (Yes, there are some examples of older women making samplers, but they are rare; in the 1790s, “our” Jane was writing early versions of Northanger Abbey, Pride and Prejudice, and Sense and Sensibility.) For this sampler to be plausibly hers, we must suppose that the 9 may originally have been an 8, and that Austen pulled out the stitches of the 8 at a later date, to conceal her real age. This is the theory put forth by those considering this may have been done by author-Jane.

Strangely, no one appears to have asked needlework experts their opinion on this theory. I am a costume and textile historian and curator of costume and textiles, including a collection of samplers and other needlework, at the DAR Museum in Washington, DC; so I’ve seen my fair share of cross-stitched letters and numerals.

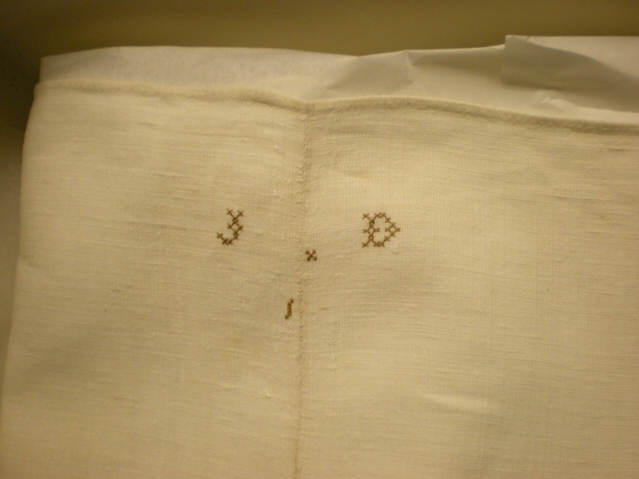

Many of the clothes, quilts, and household linens (sheets, tablecloths, etc.) I have worked with in the last 29 years have cross-stitched names or initials, and numbers, like those on samplers. That’s WHY girls made samplers: to learn how to mark the family linens for laundry and inventory.

So I’m able to look at the 1797 date and assess whether it’s been messed with.

There’s also some family history/provenance information that accompanied the sampler, but nobody seems to have followed that line of inquiry, either. Genealogy research is a huge part of what I do, so I have done some sleuthing. Ready to follow me?

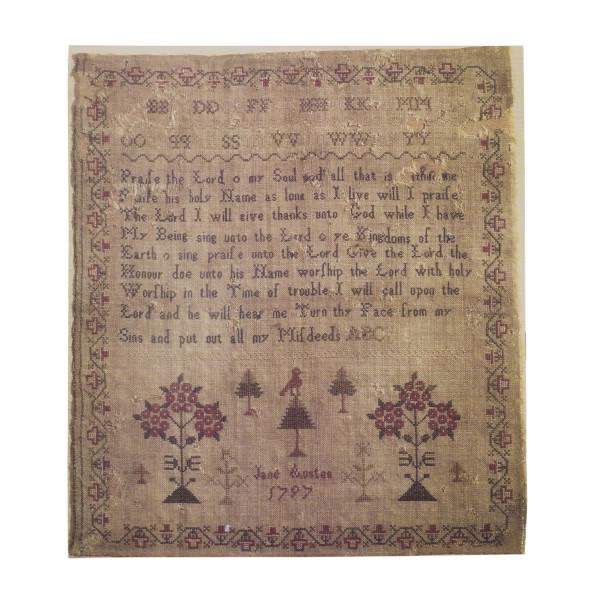

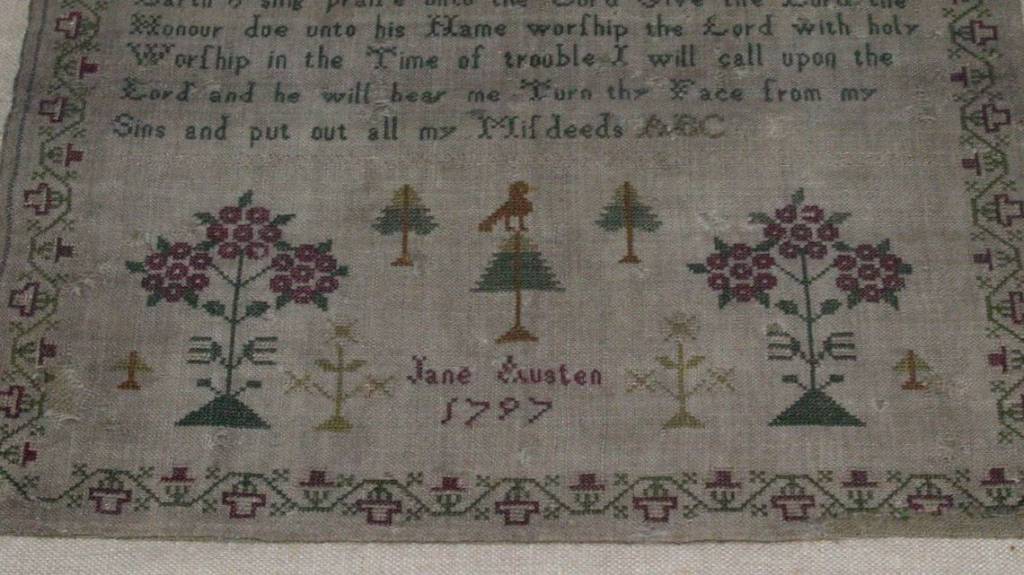

The sampler is still in private hands, and has only been on view for one day at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, as part of World Book Day in 2012. Only a very small photo was included with press releases. For a while, the Jane Austen Centre in Bath offered a poster of the sampler:

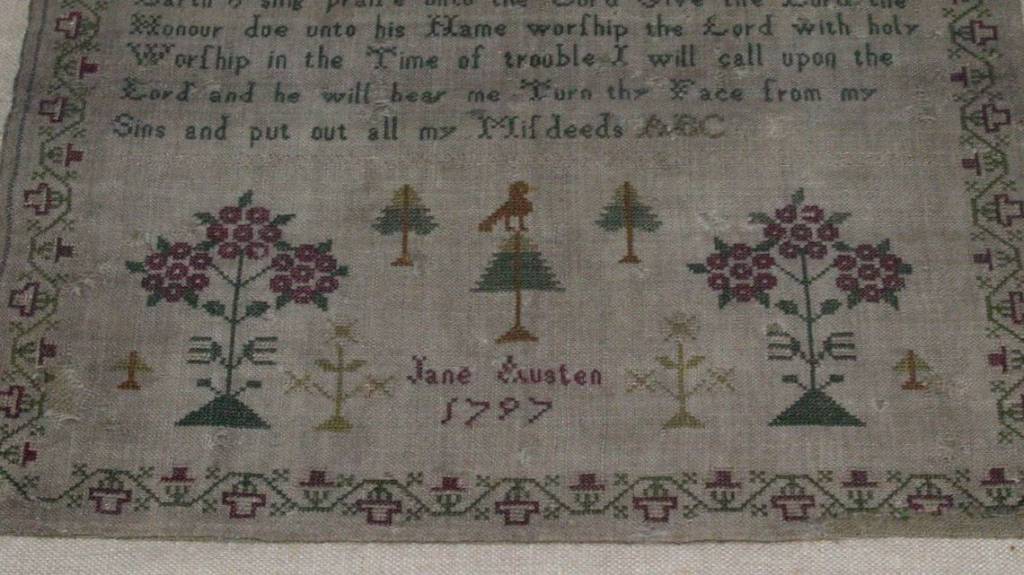

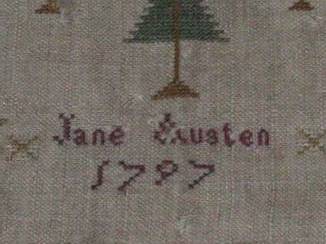

Below is a closeup of the date. The 9 looks a bit funny. Is this typical, or evidence of tampering?

(My thanks to Brenda Cox for letting me use her photos of the reproduction of the sampler; see her blog posts at https://janeaustensworld.wordpress.com/2019/04/11/jane-austens-sampler-who-stitched-it/ and https://brendascox.wordpress.com/2018/10/18/jane-austens-sampler-praising-god- part-1/ ) And here is a photo of the original from one article which appeared online when the sampler went on view in 2012:

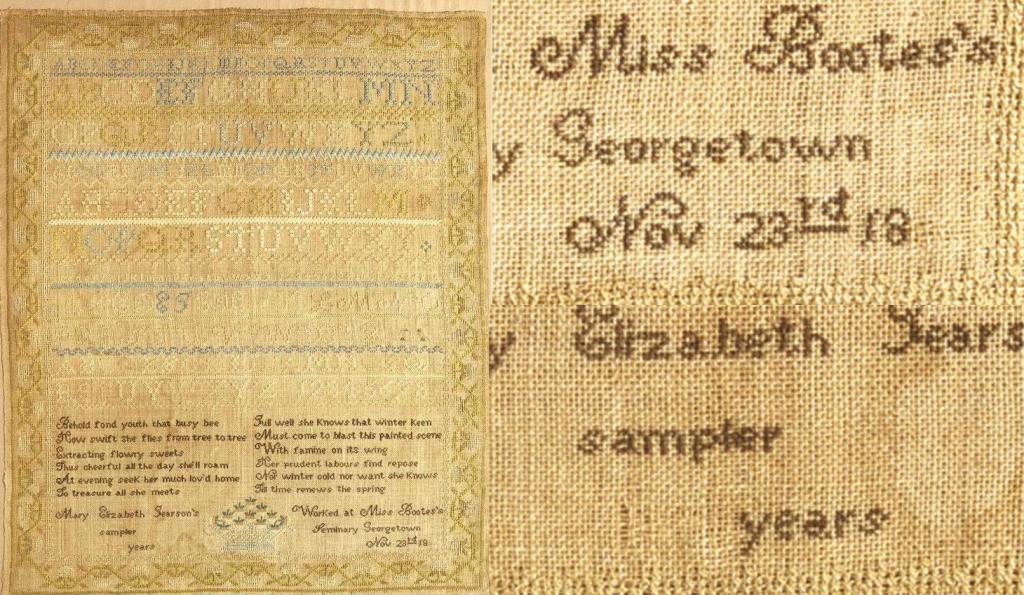

Was tampering with the date even a thing? There absolutely are samplers whose stitches were picked to conceal the date of completion, the maker’s date of birth or age, or some combination of those facts. Mary Pearson’s sampler at the DAR Museum has both her age and the date removed.

Now look at the rows of stitches which the arrows point to, below: you can’t make stitches and take them out without distorting the weave of the linen ground of the sampler, even when the linen is not very tightly woven, as we see here:

Deirdre Le Faye, the premier Austen scholar and expert, doubts the sampler was done by “our” JA because because the idea of her lying about her age seems contrary to her straightforward character. (She also mentions its errors in transcribing the Psalm excerpt: would a rector’s daughter have made these mistakes?) Those are valid objections. Mine is simply that I don’t see evidence of such tinkering with the stitches: and this is tightly-woven linen which should show evidence even more clearly than the Pearson sampler.

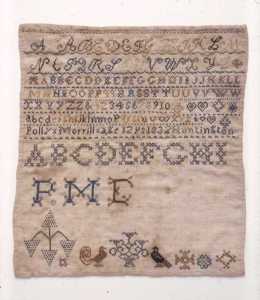

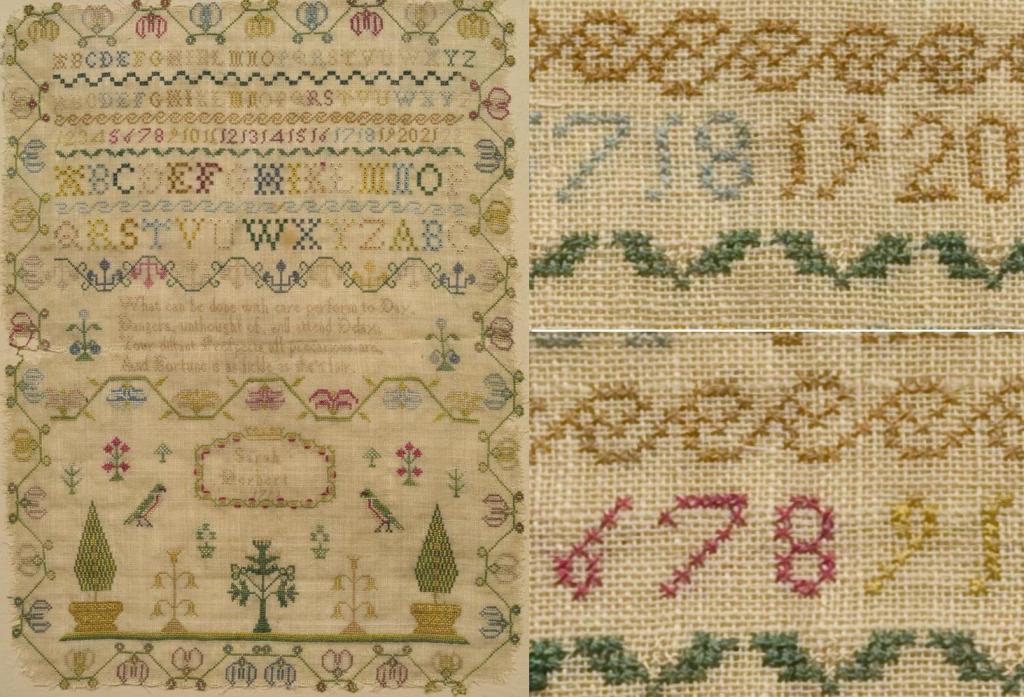

Although the 9 seems as if it should extend further diagonally to the left, I do not see evidence of the tightly-woven linen ground being distorted by the previous existence of stitches. In British samplers of this time, 9s extended diagonally down to the left beyond the confines of the circle above, as you see in the example below. This Austen sampler is, I think, merely a clumsy attempt to create that numeral in the usual way.

(By the way, I am using a British sampler of a similar date, above, to be sure we are looking at numbers as they would have been made in the same country and time frame; letter and number styles do vary slightly.) Consider too Cassandra Austen’s sampler, owned by the Jane Austen House Museum in Chawton:

Cassandra’s 9, like Sarah Herbert’s, extends considerably to the left. The 8 is extremely narrow. Taking the lower right part of the 8 away would not create a plausible 9, and there is no evidence (and no one has suggested) that stitches were added later. It seems unlikely that Jane and Cassandra Austen would have learned different stitch patterns for their numbers. Wouldn’t “our” JA, if she made a sampler, learn the same numbers as Cassandra? So I’m thinking this really was made in 1797, and this casts doubts on the attribution right away.

Now let’s look at the family history that came with the sampler. I spend a great deal of time doing genealogy research to trace the lines from donors to the makers of samplers, and fleshing out, as much as possible, the facts of the sampler makers’ lives. So it seems odd to me that no one interested in the Austen sampler has picked up these threads (sorry) and investigated this line of research. So here goes.

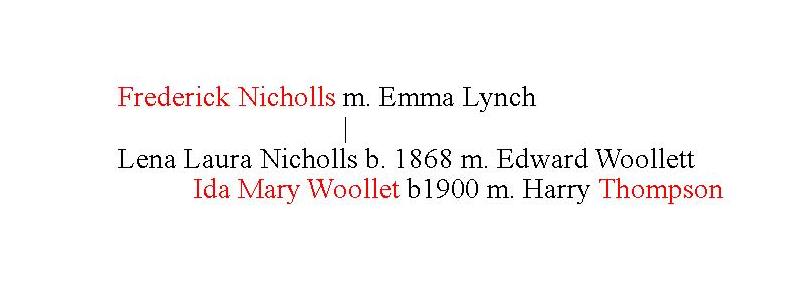

Brenda Cox’s blog post on the sampler at Jane Austen’s World (link above) records that “According to an earlier article that Le Faye refers to, in 1976 the sampler was ‘owned by a Mrs Molly Proctor, who was given it by Mrs I. Thompson of Rochester, whose grandfather, Mr Frederick Nicholls of Whitstable, was a grandson of a cousin of Jane Austen.'”

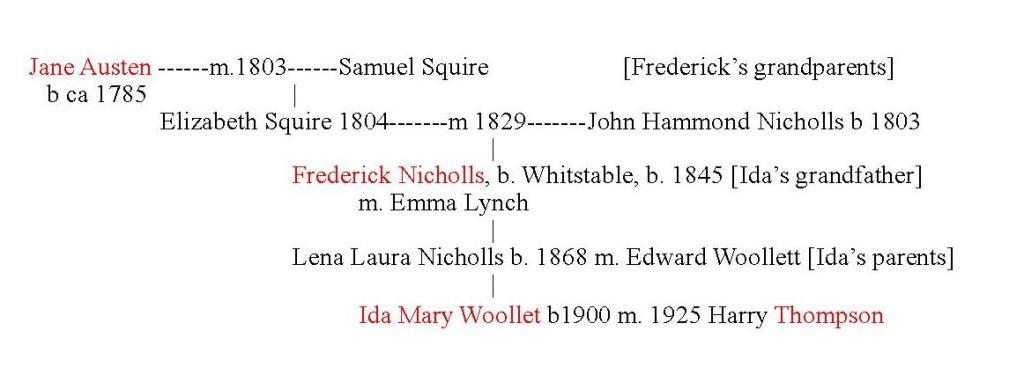

So can we trace a Mrs. I Thompson to a Frederick Nicholls, of Whitstable (on the north shore of the county of Kent in southeastern England) and go back from Frederick to a grandmother whose cousin was Jane Austen? I originally worked my way both forward and backward from Frederick Nicholls, because he’s the one we can most easily trace (men are easier to find, and we know to look in Whitstable). But I will sum up what I found by working my way back in time from Mrs. Thompson.

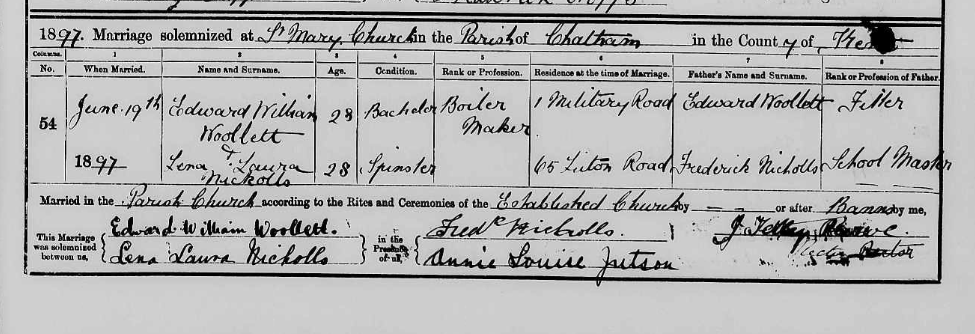

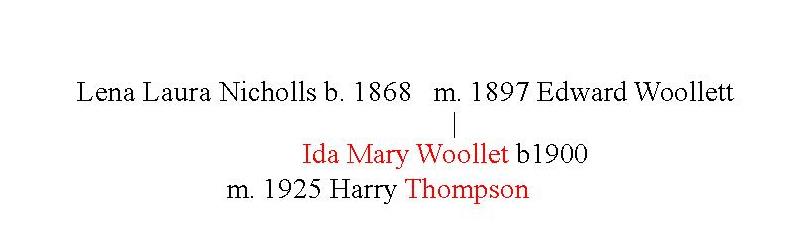

In July 1925, Ida M. Woollett married Harry H. Thompson. Ida Mary Woollett was baptized in May, 1900, in the parish of Chatham, Kent (the same county as Frederick Nicholls in the family’s note). Ida was the child of Lena Laura and Edward William Woollett; we can find their marriage in Chatham, too, in 1897. For Ida’s grandfather to be Frederick Nicholls, we need her mother’s maiden name to be Nicholls.

And look: Lena’s maiden name IS listed on her marriage certificate as Nicholls. Bingo. So, the family tree so far is:

Now– is her father Frederick, since we are hoping to find Ida’s grandfather Frederick Nicholls?

Lena’s christening record says yes: 30th August, 1868, in Pitminster, Somerset (southwestern England), Lena Laura was baptized, and her parents were Frederick and Emma (Lynch) Nicholls. In the 1881 census, they all lived in Pitminster, Somerset.

But they’re in Somerset, and Frederick is supposed to be from Whitstable, Kent, over 200 miles away.

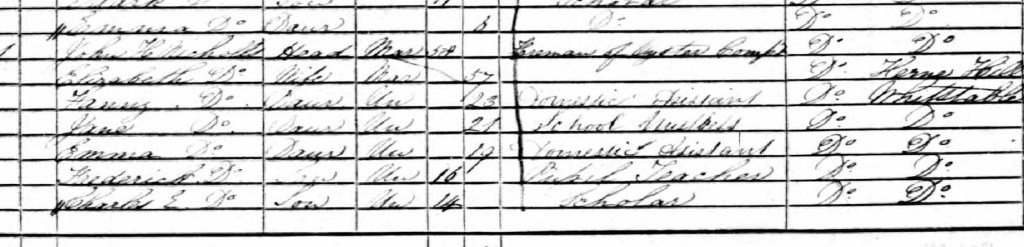

Never fear: Frederick is indeed in Whitstable in the 1851 and 1861 censuses with his parents, John Hammond Nicholls and Elizabeth Nicholls. In 1861, Frederick was 16 and a “pupil teacher.” Deirdre Le Faye kindly informs me that “in 1861 a lower middle class youth of 16 would not be attending school purely as a scholar. … Intelligent teenagers were considered perfectly capable of teaching younger children, while perhaps learning a little more, say, commercial arithmetic, themselves, before going on to apprenticeships.” Two of his sisters are listed as “domestic assistants” (servants? Or just helping at home?) and a third is a school mistress (teacher).

Their father John is a “freeman of Oyster fishery.” The National Archives, in its introduction to the Whitstable Oyster Fishery’s records, explains: “The Company of Free Fishers and Dredgers…allowed the ‘eldest son of a fisherman at 16 and others at 21’ to become Freemen, thus bestowing upon them the right to farm oysters.”

Oysters (once, remember, a poor man’s food) have been fished in Whitstable since the Middle Ages; the Whitstable Oyster Fishery company was founded in 1793. More about this at: https://www.whitstable.rocks/history/ . It’s always interesting to know about the sampler maker’s background, but here, it is worth noting the head of the family’s occupation; oyster fishermen seem unlikely to have been connected to the author Jane Austen, who came from the gentry. As a social historian, however, I am intrigued to see that someone in this class is making a very pretty sampler.

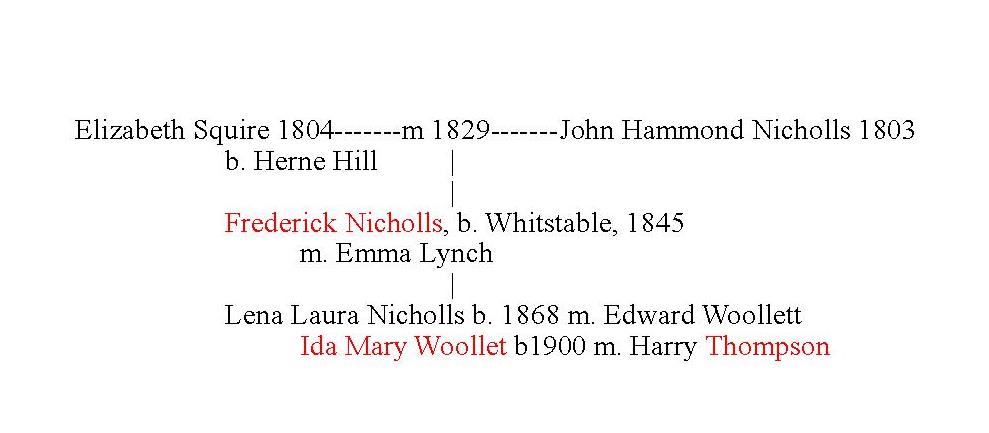

In the census, Elizabeth Nicholls’s birthplace is listed as Herne Hill (now Hernhill) Kent. Off we go to Herne Hill in search of a marriage record, as most women are married in their home parish. Yes, there she is in an 1829 marriage record which lists her maiden name as Squire. We can now fill in the family tree some more with Frederick’s parents’ births and marriage:

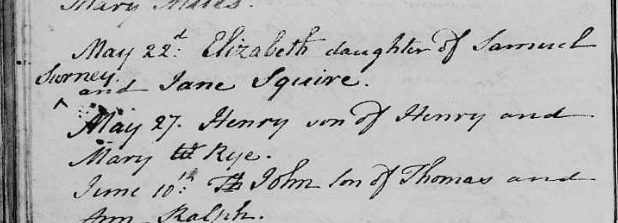

Now we need for either John’s or Elizabeth’s mother to be related to Austen, as we are looking for the “grandmother of Frederick Nicholls” –this is the sampler generation. Elizabeth’s baptism record in Herne Hill in 1804 lists her parents: Samuel Surney (elsewhere in records, Surey or Sarny) Squire and Jane. JANE! Wait–Jane WHO? What was Jane’s maiden name?

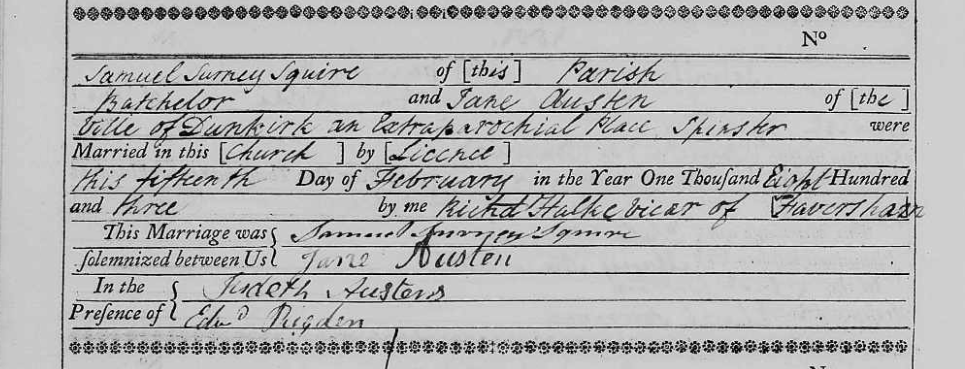

Herne Hill church records include the marriage on 12 February, 1803, of Samuel Surney Squire age 26 to Jane AUSTEN, age 18, the daughter of Daniel A. Austen. JANE AUSTEN: FOUND.

The family history said Frederick’s grandmother was a cousin of Jane Austen, not that she WAS Jane Austen. Knowing Austen never had children, they’d have to claim indirect connection to her, not lineal descent. But as we see, Frederick Nicholls’s grandmother was in fact [a] Jane Austen, evidently the sampler maker herself.

So here’s the family tree from Ida Thompson to grandfather Frederick to his grandmother–Jane Austen:

Oh dear. Good news: we have connected all the dots and confirmed the sampler’s oral family history.

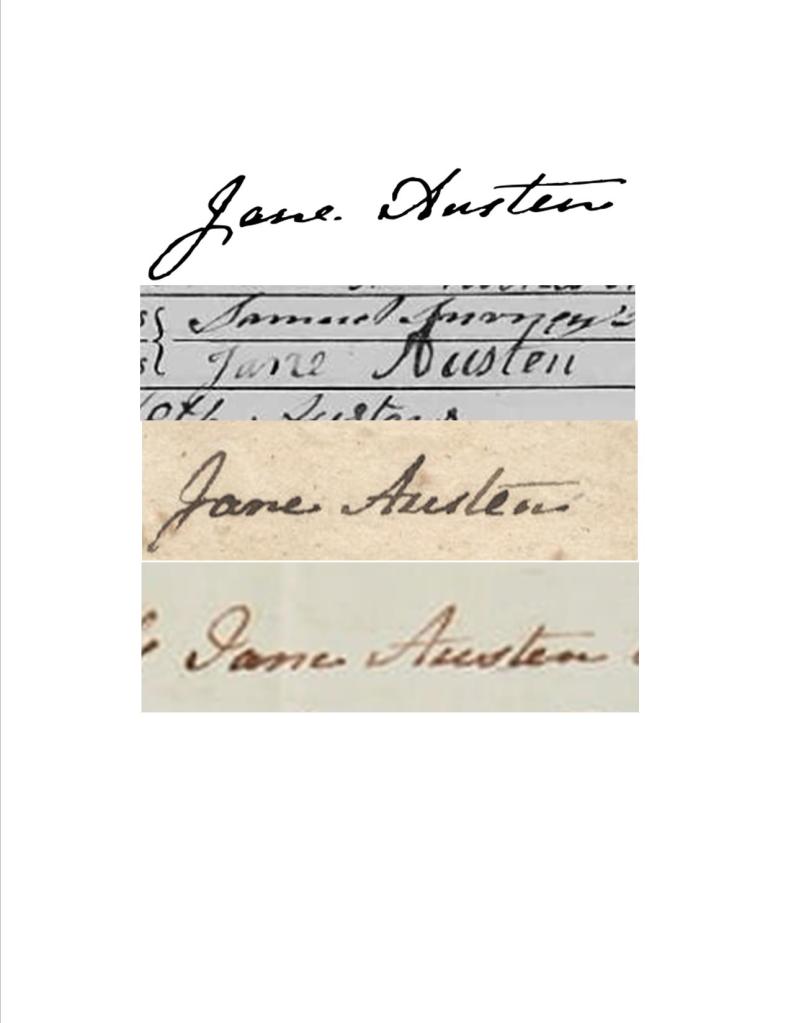

The bad news: This is not “our” Jane Austen. Compare too her signatures to three known signatures by the author: Jane Austen Squire’s is the second from the top. The top is from Jane Austen the author’s will, the other two are from letters of hers sold recently at auctions.

I’m no expert in handwriting, but simple observation shows that “our” Jane has a large, full loop on her J, and narrower letters; she crosses the capital A with a separate stroke, where Jane A. Squire keeps her pen on the paper to loop back to cross it. Her lower case letters are rounder and overall the signature has a look of someone who does not write often, or with great ease. I’m not including this as conclusive, strong proof of anything, but it’s worth noting.

If this Jane married in 1803, she was probably born about 18-20 years previously: 1783 to 1785. She’d be 12 to 14 in 1797, about the right age for making such a sampler. I cannot find a baptism record for her, nor a definite marriage record for her parents (possibly a 1781 marriage in Canterbury, Kent, of a Daniel Austen to an Ann Bowles, is correct).

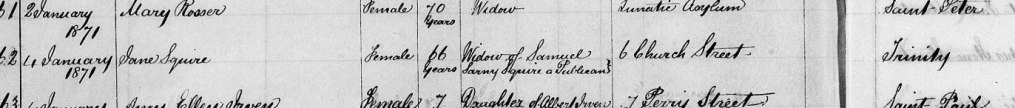

What more can we learn about this Jane? Herne Hill baptism records list Jane and Samuel’s children Elizabeth in 1804; Harriet in 1805; Samuel in 1806; and Septima in 1808. Young Samuel is a servant in Herne Hill in the 1851 census; we know Elizabeth married John Nicholls and lived in Whitstable; the others have proved harder to trace. An 1871 death record for Jane, widow of Samuel Sarny Squire, in Maidstone, Kent, lists her age as 66, putting her date of birth at about 1805, which is wildly incorrect. Samuel *Sarney* Squire is too distinct a name for mistaken identity. Could they have meant she died at age 86, taking us to 1785? Or did Jane Austen Squire die and Samuel remarry another younger Jane? This seems far-fetched. It is definitely not an incorrect transcription:

Why do we care, now we’ve seen it can’t be “our” Jane? Partly to fill in the gaps and provide further documentation of who she was, but also to establish the social class of the Squires. This death record lists Samuel Sarny Squire was “a Publican,” i.e., he owned a pub. A fine fellow I am sure, but a publican, father-in-law of an oyster freeman, was not rubbing elbows with our Austens of Godmersham Park, Chawton House, and the like.

It’s worth adding that it is not far-fetched to suppose this Jane was making a sampler. A simpler marking sampler with alphabets and numbers would be needed by any young woman who could expect to mark all her family’s undergarments, and bed and table linens, with cross-stitched initials and numbers.

As for the fancier style of this sampler: the caricaturist James Gillray in the print below mocks “Farmer Giles” (an archetype of the yeoman farmer class in Britain) for having aspirations above his class, sending his daughter to boarding school to acquire some gentility. Something has to be pervasive for a caricaturist to bother mocking it.

Occupying the center of the picture, and pride of place in the parlor, is her sampler, a proof of her accomplishments as much as her piano-playing is.

It would be wonderful to ascribe this sampler to THE Jane Austen, since so few artifacts survive which belonged to her. Sadly, however, it seems clear that the family history, carefully passed down, leads us to a different conclusion. Not to an attribution to a cousin in Kent, as Deirdre Le Faye suggested, but to an entirely different, unrelated Jane of a significantly different social class. It is an interesting object on its own merits, telling a story of the middling class in England at the turn of the nineteenth century. (I am not completely confident that I know how to label the English classes at this time, which were surely more nuanced than America’s. I’m going to say “middling” and wait to be corrected if need be.) But we need to abandon it as an Austen-of-Chawton relic.

Great sleuthing! There must have been many more Jane Austens than we realise and a wrong assumption can be easily made. Thank you for providing a well researched answer to this one.

LikeLike

Thanks and you’re welcome! Indeed Austen was not a terribly uncommon name.

LikeLike

wow ! that is some amazing research.

(can you say rabbit hole?)

congrats on your willingness to pursue to the end…

LikeLike

thanks!! Willing–heck! it’s a red flag to a bull if I see a genealogy trail…

LikeLike

Willing? I love a good rabbit hole, cant’ stay away, ha!

LikeLike

Wow, great sleuthing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! I love a good mystery

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating! Thanks, Alden, for another great read!

Betty Mahoney

LikeLike

Hooray for honest research, both of the article and the genealogy! It would have been wonderful if the sampler had been made by Jane Austen the writer, but Truth is more important than sentiment! I would like to know more about how Victorian linen was marked. The passage in Trollope’s “Can You Forgive Her?” in which Mrs. Greenhow and her maid discuss changing the markings on the sheets has always intrigued me. They talk of having to “fine-draw” the embroidery. Fascinating!

LikeLike

Thank you! Yes, it would be wonderful but alas… I will have to go back and reread that passage in Trollope, don’t know why they’d be changing the markings…

LikeLike

Here is the passage. Less than a paragraph. Mrs. Greenow (I misspelled her name before.) doesn’t believe in wasting anything.

Large trunks of household linen had arrived, and all this linen was marked with the name of Greenow; Greenow, 5.58; Greenow, 7.52; and a good deal had to be done before this ancient wealth of housewifery could probably be converted to Bellfield purposes. “We must cut out the pieces, Jeannette, and work ’em in again ever so carefully,” said the widow, after some painful consideration. “It will always show,” said Jeannette, shaking her head. “But the other would show worse,” said the widow; “and if you finedraw it, not one person in ten will notice it. We’d always put them on with the name to the feet, you know.”

LikeLike

wow, cool! I need to do a post on laundry markings I guess. I think she’s proposing cutting and pulling (drawing) the threads of the inscriptions of name and inventory numbers, and then stitching the Bellfield name and numbers. Either that, or it’s written in ink and will require actual cutting out and replacing a patch. Haven’t seen “finedraw” used before and not sure whether it’s literal drawing or, as I think, drawing as in pulling threads. Rabbit hole!

LikeLike

Enjoy yourself, and let me know the results!

LikeLike

Oh my! That was fascinating! Thank you

LikeLike

🙂

LikeLike

How interesting! I’ve dabbled in embroidery and cross stitch for most of my life and 9’s are definitely odd to stitch. For those who argue otherwise, I’d like to see them cross stitch a 9 more “normally.” =)

LikeLike

I loved watching your fine mind work as you follow the breadcrumbs back to the answer. What fun! It was disappointing not to be “our” Jane Austen, but I very much enjoyed the ride. Thank you!

LikeLike

Thank YOU! CO

LikeLike

That was supposed to be XO but I haven’t figured out how to edit/delete on the app…

LikeLike

As a Jane Austen fan with a long-standing interest in (and small collection of) samplers, I found that absolutely fascinating! Thank you very much.

LikeLike

I’m so glad, thank you!

LikeLike

I’ve just found your blog and am in awe over the research you’ve done! You certainly have me convinced. Not to mention how difficult it would be to fudge your age when you have so many relatives who know better! “Fine drawing” is actually a mending technique. I’m obsessed with “plain sewing” and have 19th century books with illustrations and samples of it. The work really could be almost invisible when well done. My attempts do not fall into that category!

LikeLike

Thanks so much! So true about fudging age but there are definitely some samplers where it’s just been taken out altogether. Not nice to ask a lady her age and all that! Anyway as I said I just see no physical/visible evidence here. Would love to know titles of some of those 19c books, in case they are ones I have not come across. Happy to continue chat at aobrien@dar.org if you like!

LikeLike

Done! 🙂

LikeLike